The Kokoro Files is a series that tells stories of everyday people and their connection to Japan. Some are drawn to the Land of the Rising Sun for the food, while others feel connected to the music. Michael Graham was inspired by Japanese music, to the point that he was compelled to learn how to play traditional instruments like the koto.

Michael was kind enough to share his musical experiences with Yamato Magazine and explain how he became part of a Taiko drum band.

Thanks for taking the time to chat Michael. Japan inspires people in a variety of ways and it’d be great to hear where your interest in the country first came from.

I went backpacking around the world for a couple of years after university and passed through Japan for a month, on the way to Korea and China. I was already interested in the allure of exotic and especially eastern cultures, which had rather guided my itinerary, and found the country very friendly and welcoming.

Although there were a lot of new experiences and differences, my initial reaction was slightly muted by the overwhelming westernisation of arrival cities, such as Tokyo. I could see that there was a veneer of the country that was evident to a tourist, however there was also a deeper, more tradition social structure underpinning the actions of Japanese people, which was largely inaccessible on such a brief visit. I wanted to understand these more, so went back to get under the surface structure of the modern image. The original planned one year living in Japan turned into about seven.

You mentioned you have a background in Japanese instruments like the koto and shamisen. How important are both musical styles in Japanese culture?

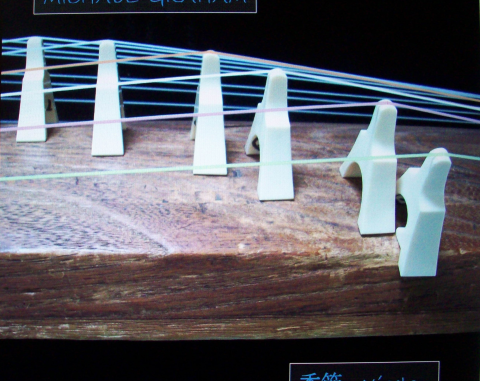

The two instruments traditionally have different starting points. The koto has an elite history, starting out as one of the instruments that would make up a court orchestra, playing at the imperial palaces, during the Heian era, a thousand years ago. By the 1600s it was one of the accomplishments learnt by noble families, and it’s from this point on that the repertoire that is played today originates.

The shamisen by contrast, is much more an instrument of the people. Being easier to carry around, it travelled across the country with minstrels and therefore grew to become associated with providing the accompaniment to folk songs and dances, cropping up at festivals, kabuki performances and as entertainment in tea houses, played by geisha.

Both instruments suffered a downturn in popularity at the close of the feudal era and the opening up of Japan to Western influence, (1860s onwards), but have undergone various re-discoveries and abandonments over the years, as popularity has ebbed and flowed. They will be forever connected in the mind with their distant past, and therefore inextricably linked to Japanese cultural identity. The sound of either instrument is enough to evoke a recognition of the country, in both Japanese and western people.

Does it take a lot of preparation to master the instruments?

I play a lot of world music instruments, most of them stringed, so when I arrived in Japan I was keen to learn the traditional instruments. As I already played guitar, banjo and mandolin, I started on the shamisen because of similarities to instruments I previously knew. Getting used to it being a fretless fingerboard was a challenge, as was handling the bachi, (an oversized plectrum, used in the right hand to pick the strings).

In comparison, the koto is different to anything else I was familiar with. However, it is quite an easy instrument to pick up. Although the 13 strings look confusing at first, each only produces one note, (unlike most string instruments where one string is used for a range of notes).

Like any instrument, both of them will have that transition period where playing them seems un-natural, until muscle memory develops a sense of what feels normal. But the main difficulties to learning are not to do with playing technique.

For me the barriers I had to overcome were threefold: Firstly, traditional instruments are often taught traditionally, in other words, lessons will take place sat on the floor in seiza style, (sitting on the knees). Slowly, I built up the time I could do this without needing a break to stretch, so I could sit a whole 45 minute lesson without interruption.

Secondly, Japanese teaching style is very different to Western methods. Often little, if any, explanation was given. The teacher would demonstrate a perfect version of what was expected and the pressure was on me, as the pupil, to work out how to copy the example. If I didn’t get it, the teacher would do it again, rather than help out with advice on what needed to be corrected.

The third difficulty was that of knowing the tunes. As I had not grown up in Japan, tunes which were familiar to Japanese people were totally new to me, so before I started to learn a piece, I would ask the teacher to play it, so that I could record it and then play it back to myself at home, learning the tune in my memory.

Another important difference to note when studying any country’s traditional instruments, is that they often won’t use western standard notation for the written musical scores. In Japan, each instrument has its own scoring system, so a shamisen score looks different to a koto score, which in turn looks different to a shakuhachi score, even for the same piece of music. Learning to read the scores can be a challenge, but since they relate specifically to the instrument they are designed for, they are very logical.

I’ve heard you play with UK-based Taiko drumming group Kaminari Taiko. How did you become involved with the group?

When I returned to the UK, after living in Japan for a few years, I shipped back a shamisen and koto. I made a video of my playing and posted it on YouTube, so that my teacher in Japan could see the instruments had made it safely to the UK. This was seen by another Japanese lady who, by utter coincidence, lived in the next town to me, in the UK. She informed me of an open day event taking place for a Japanese school based in York.

I went along primarily to maintain my connection with Japan and saw Kaminari playing at the event. After their performance, I got taking to Mary Murata, from Kaminari, who also organised a Japanese society, that met once a month. It was at one of the meetings that she mentioned that Kaminari were rehearsing a show involving drumming and poetry, but there was a disconnect between the calm poems and the furious drums.

I was invited along to a rehearsal, with the intension of providing a more harmonious link between the two elements. After the project came to an end, I still join Kaminari for some performances in order to add a change of pace and dynamic to certain shows.

Do you feel that subtler instruments like the koto bring a different dimension to something as intense as a Taiko drum performance?

Yes, definitely. Taiko performances can be overwhelming, not just aurally but visually as well. There is the thundering sound of the drums but also there is an energetic choreography that makes a show quite a spectacle.

When the shamisen and the koto enter, it’s like a calm in the middle of a storm and it creates a dynamic contrast, which gives audiences breathing space. It also gives them an opportunity to experience a broader range of Japanese instruments and sounds, and adds contrast between the drums, which are rhythm instruments and the koto and shamisen which are melody instruments.

When you’re playing, what kind of mood are you trying to evoke in listeners?

Generally, when I perform, there are a number of aims to the performance. The nature of the instrument’s sound immediately creates an Oriental atmosphere and imagery, so whether I’m playing a traditional piece, or one of my own compositions, I maintain the traditional pentatonic (5 note) scale, for the tuning. A lot of Japanese culture is geared around nature and the arts play their part in reflecting this, so often I ask audiences to imagine what is happening in the music or give clues when I’m introducing a piece, as to the season or scene from the natural world that it evokes.

In solo performances I often talk between tunes, educating listeners about the instruments, their history and how they link to Japanese culture. Hopefully, a relaxing feeling will come over people and I even advise that the audience close their eyes to fully experience a piece.

Lastly, performers in Japan are taught to make performances unique to the place or situation that they are playing in. To do this we can adapt the volume or timing of notes differently to how we might have performed a tune before. For example, I once played a piece in a cathedral, where the reverberation was so good that I left a fraction of a second longer of silence between each note, so that they could echo around the space. Playing the same piece outside, on a windy day, I played with a shortened space between each note, because the sound was taken away so quickly by intermittent gusts.

Do you believe that modern day music has influenced the playing style of traditional Japanese instruments?

Everybody starts by learning the basics and these are the traditional tunes and techniques. As such there is still a very solid, unaltered foundation within Japanese music and not much has changed.

The main influence modern day music has had has been on composition. After Japan opened up to the west, Japanese composers travelled to Europe to study classical music and brought back themes and melodic ideas that blended with and altered future work written for tradition instruments.

One result of more modern music on koto technique is that of two hand counter melody. Whereas in traditional playing (pre-1870s) only the right hand played the strings, recent compositions have the left hand crossing over and playing at the same time. The result is more complex melodies from just a solo performer, rather than having a second koto player playing a second part, in duet.

Has the shamisen seen any crossover into other musical genres?

Not at any significant level. Several types of traditional instruments have appeared in Jazz ensembles or alongside a classical orchestra, but these fusions often seem to be one off experiments, rather than attempts at long-term, sustained projects and therefore remain the exception. The most notable occurrences have been in blending traditional sounds with modern music, often with the traditional instruments playing a melody over a synth background, creating more of a kind of ‘atmosphere’ piece.

Some notable artists have had minor success bringing this approach to popular attention, such as Rin, Zan and Agatsuma. The Wagaki Band have also combined traditional instruments with rock instruments (electric guitar and drums), to deliver a more powerful fusion.

Are there any musicians that have influenced you in your creative process?

I wouldn’t say that there are any individuals that have influenced me, rather I was influenced by different styles of traditional music. I started learning ‘naga-uta’ shamisen, the style of long songs used in kabuki plays.

However, since these songs can be 40 minutes long, with very little structure to guide the player, I switched to ‘min-yo’, the shorter folk song style, after purchasing a collection of folk music CDs. These types of song have a familiar pattern of repetition, over a shorter cycle, making them far easier to learn.

In addition, Japanese artistic endeavours, (music, painting, clothing, etc), have continually been influenced by and reference nature. Details, in the works, are closely linked to the seasons, sounds or visual aspects of the environment that the artist wishes to include, as clues, in their creation. As such, when I compose, I try to use the sounds and notes of the instruments as a descriptive tool.

Where in Japan would you recommend to go and see a traditional Japanese musical performance?

Admittedly it can be quite difficult to find performances, unless you are well networked to someone in the know, or stumble on a festival or recital, more by accident than by design. You could quite easily visit Japan and not see any traditional music or other performances. If you are in high density tourist areas, such as Tokyo, Kyoto or Osaka, then make contact with the Tourist Information Centre. They will have information on scheduled events, such as the regular kabuki shows at Kabuki-za in Tokyo, or the geisha shows at Gion corner in Kyoto.

If you find yourself in more provincial cities, try the bunka centres. These are culture centres that every medium to large town will have. They have either shows or workshops and if you are staying more long term, they will know teachers that offer lessons. The main festival season is during the summer and it is hard to move around the country without finding a nearby area holding one. Here you will usually get to see some dancing accompanied by music, either fue (bamboo folk flutes), singing or taiko (drums).

Michael Graham is a UK-based musician who specialises in traditional Japanese instruments. His CD of original compositions for koto, called ‘Kisetsu’ (Seasons) is available to buy now.

Great post 🙂

LikeLike

What a fascinating and interesting post! Thank you for sharing and thank you for following BrewNSpew. 🙂

LikeLike

I’m so glad you popped over to my site so I could see yours. This is AWESOME! And I ADORE the art work at the top.

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed reading and your website is great too!

LikeLiked by 1 person